Demystifying MOOCs: An Eye-Opening Ethnographic Study of Online Education

Christina Wasson (Professor of Anthropology, University of North Texas) investigates communication, collaboration, and community-building in face-to-face and virtual settings. She was a founding member of the EPIC Steering Committee.

Christina Wasson (Professor of Anthropology, University of North Texas) investigates communication, collaboration, and community-building in face-to-face and virtual settings. She was a founding member of the EPIC Steering Committee.

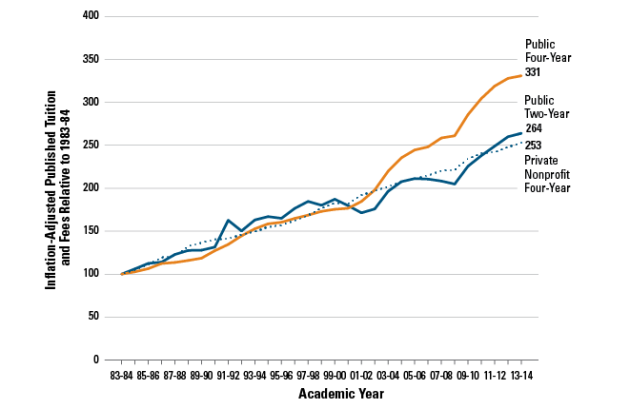

Editors note: A collaboration of social, economic, and technological factors have contributed to the flourishing of MOOC’s – massive online open courses. With public universities’ tuition more than tripling since the mid-80’s, fewer people have been able to access a traditional four-year undergraduate education. While this seemingly places MOOCs in a position of strength, this fast-moving frontier of education is still young, and suffers from design issues.

One such issue lies in the fact that while students are beginning MOOCs in record numbers, far fewer actually finish. This and other challenges plays to Christina Wasson’s strengths, and particularly her penchant for researching “communication, collaboration, and community-building.” Here, she gets beneath statistics and surface level assumptions, employing ethnographic research techniques to study the students in her course. Her ethnographic study of online learning revealed serious limitations to the potential of MOOCs.

As one of the founders of EPIC and lead developer of the online Master’s in Anthropology at the University of Texas, her considerable experience in academia and online education come through in her post this month.

For more posts from this EPIC edition curated by editor Tricia Wang (who gave the opening keynoted talk at EPIC this year), follow this link.

ECONOMIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL UPHEAVALS

The coexistence of destruction and creation,

Image 70 in Jung’s The Red Book

People are inventing creative ways to respond to today’s economic and technological upheavals. In the American educational sector, we see the extraordinarily rapid rise of MOOCs – Massive Open Online Courses – as a potential way to manage escalating college costs. The New York Times declared 2012 the “Year of the MOOC,” and Time Magazine heralded MOOCs as “revolutionary, the future, the single most important experiment that will democratize higher education and end the era of overpriced colleges.”

But what do MOOCs look like from the students’ point of view – the users? Considering that typically 85% of students drop out, it would be useful to find out how they experience MOOCs. As of fall 2013, no substantive studies had been published about MOOCs targeted at college students. However, I did lead an ethnographic study of a small-enrollment online course, and its findings have clear applications for MOOCs.

THE PROMISE OF MOOCS

MOOCs have captured the imagination of the business press, venture capitalists, and university leaders because they seem to solve knotty problems created by shifts in educations costs, while generating business opportunities.

In the US, states have increasingly reduced their subsidization of public universities, shifting the financial burden onto individual students. As states provided less funding, tuition went up. This graph from the College Board shows that even adjusted for inflation, tuition at public universities has more than tripled since 1984.

Recent Comments