Ethnography Beyond Text and Print: How the digital can transform ethnographic expressions

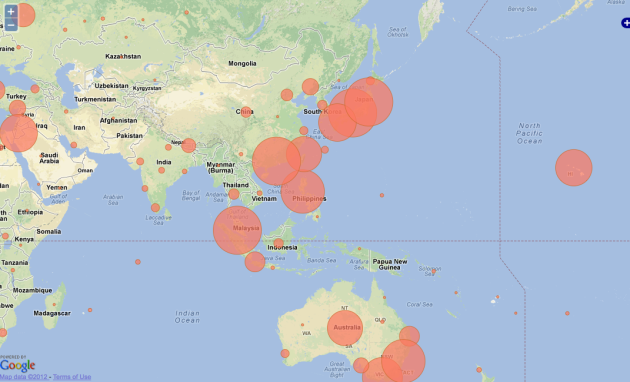

Editor’s note: This is the final post in Wendy Hsu‘s 4-part series, On Digital Ethnography. Wendy asks what does an ethnography beyond text and print look like? To answer this question, she calls on us to reconsider what counts as “ethnographic knowledge.” Wendy provides examples of collaborative multimedia projects that are just as “ethnographic” in nature as a traditional ethnographic monograph. The first post in the On Digital Ethnography series called for ethnographers to use computer software, the second post introduced readers to her methods of deploying computer programs to collect quantitative data, and the third post urged ethnographers to pay more attention to the sounds, sights, and other material aspects of our field research. Wendy @WendyFHsu is an ACLS Public Fellow working with the City of LA Department of Cultural Affair. She recently finished her term as a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Center of Digital Learning + Research at Occidental College and completed her dissertation on the spread of independent rock music.

Editor’s note: This is the final post in Wendy Hsu‘s 4-part series, On Digital Ethnography. Wendy asks what does an ethnography beyond text and print look like? To answer this question, she calls on us to reconsider what counts as “ethnographic knowledge.” Wendy provides examples of collaborative multimedia projects that are just as “ethnographic” in nature as a traditional ethnographic monograph. The first post in the On Digital Ethnography series called for ethnographers to use computer software, the second post introduced readers to her methods of deploying computer programs to collect quantitative data, and the third post urged ethnographers to pay more attention to the sounds, sights, and other material aspects of our field research. Wendy @WendyFHsu is an ACLS Public Fellow working with the City of LA Department of Cultural Affair. She recently finished her term as a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Center of Digital Learning + Research at Occidental College and completed her dissertation on the spread of independent rock music.

Yea, as a fellow with the City of LA Department of Cultural Affairs, I have a mission to innovate and technologize the department. I’m spearheading the department’s web redesign project — thinking about how to better articulate our work, outreach to constituents, and digitize some of our services. I’m still wearing my ethnographer’s hat, thinking about how to cull through the vast amount of data related to arts and culture here at the city, and leveraging social media and other mobile/digital data to better understand the impact of our work. I’m also working with the City’s Information Technology Agency to join efforts in their Open Data initiative with the goal to augment civic participation through innovation projects like civic hacking.

Ethnography means fieldwork or field research – a set of research practices applied for the purpose of acquiring data; but the term also refers to the descriptive representation of one’s fieldwork. In my series on digital ethnography so far, I have discussed how digital and computational methods could enhance how we as ethnographers acquire, process, explore, and re-scale field data. In this last post, I will shift my focus away from field research to discuss the process of “writing up” field findings. I ask: How might the digital transform the way we communicate ethnographic information and knowledge?

I pick up from where Jenna Burrell left off in her recent post “Persuasive Formats” to interrogate the medium of writing as a privileged mode of expression of academic ethnographic practices. Early in graduate school, I learned that the eventual outcome of doing ethnographic research is the publication of a monograph. People around me use the word “monograph” to refer to a book-length treatment of research of a single subject published by an academic press [they looks something like what’s shown in Figure 1]. This is, however, one of many definitions of monograph (apparently humanists have a definition stricter than scientists and librarians). Burrell attributes the scarcity of academic publication to economic reasons, and suggests online publishing as a potential solution to remedy the cost of print-based publishing and to enable the integration of visual materials in publications.

Ethnography, based on the Greek root of “graph,” means the representation of field experience, findings, and analysis through the medium of writing. But writing, denoted by the word “graph,” may have always been used to refer to textual means of representation (i.e. what we think of as writing), but there are instances of this root referring to non-textual means such as photograph, lithograph, phonograph, heliograph, etc. The ambiguity of writing as a medium that can be either textual or nontextual has been with us since the invention of these words.

I’m not advocating for abolishing academic book publishing. Others have and have discussed the economic and ideological structure that supports academic publishing and valorizes the monograph.) Instead, I want to make room for a serious consideration of ethnographic expressions that are not strictly based in text, either in the form of a book or a journal article, but are dynamically articulated in interactive and multimediated systems afforded by digital technology. Some of you might find this claim to be professionally irrelevant to you, if your preoccupation with ethnography falls outside of the academy. But the concerns and techniques that I will talk about may pique your interest as you consider the ways to communicate findings and analysis to clients, collaborators, and stakeholders.

If we open up the definition of ethnography beyond text and print, then we can start to envision a media-enriched, performative, and collaborative space for ethnographers to convey what they have encountered, experienced, and postulated. Utilizing the affordances of digital media, ethnographic knowledge can be stored, expressed, and shared in ways beyond a single medium, direction, and user. In what follows, I will outline a few computational practices, platforms, and projects to illustrate these points. Read More…

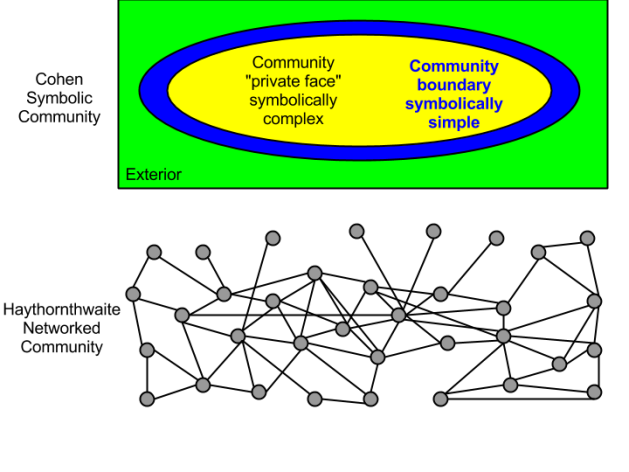

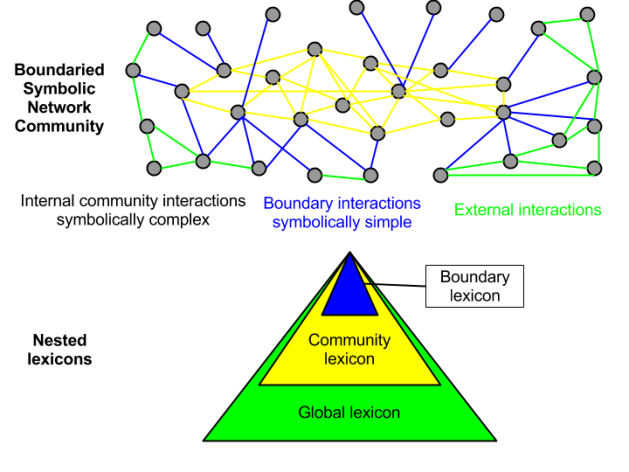

I believe we have an opportunity to use the wealth of data available now to really advance social science. But the reality is our research will, if successful, be used for political manipulation, commercial advertising, and other kinds of social manipulation and control. For me, this makes it imperative that I present my research to the public. If I work on methods for on-line community detection, I should try to make those insights usable by communities to understand themselves and evade detection if they desire.

I believe we have an opportunity to use the wealth of data available now to really advance social science. But the reality is our research will, if successful, be used for political manipulation, commercial advertising, and other kinds of social manipulation and control. For me, this makes it imperative that I present my research to the public. If I work on methods for on-line community detection, I should try to make those insights usable by communities to understand themselves and evade detection if they desire. I thought I had found a nexus of this kind of noisy on-line behavior on Twitter. If what I was seeing was a community at all, it was a community of chaos and exploration. And it knew it. I had read the term “weird twitter” in

I thought I had found a nexus of this kind of noisy on-line behavior on Twitter. If what I was seeing was a community at all, it was a community of chaos and exploration. And it knew it. I had read the term “weird twitter” in

Recent Comments